Image: The Provincial Museum of Kymenlaakso (PMK)

THE JOURNEY OF THE WOOD

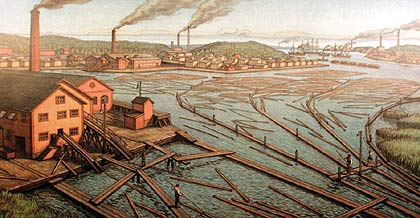

It was all based on waterways. The River Kymi waterway system was an excellent transport route from the inland forests to the coast, and the sea linked Finland to the rest of the world.

In the 19th century Finland was an autonomous grand duchy under Russia. The economic liberalism that prevailed in the latter part of the century encouraged enterprise. When the massive world economic boom came to a peak in 1873, the demand for Finnish timber seemed endless and prices doubled. Now if ever was the time to make money. The stampede by investors hoping to make a favourable investment began.

The business concept can be seen on the map of Finland: the large timber reserves would be transported along the rivers to the coast, sawmills would be built on the river deltas to refine the timber, and the final product would then be sold abroad for a good profit.

The River Kymi delta area, the present-day city of Kotka, went through unprecedented industrial growth between 1871 and 1876, when nine steam-driven sawmills were founded. Their capacity totalled just over one-quarter of the production of the whole country.

This sector of industry was dangerously susceptible to economic fluctuations. Furthermore, a fundamental problem lay in the slow turn-around of capital; the timber cycle from the forest via the sawmill to the finished product loaded on the ship took three years. By the beginning of 1879 only one of the sawmills was still operating. In 1886 the long and heavy recession hit rock bottom, after which prices went up and an economic-politically stable period began. Economic recovery followed, and supply and demand reached a balance.

The workforce in the sawmill and in the harbour as well as the seamen consisted partly of people from the local rural population, but mostly of people who had moved from elsewhere. With the closure of the sawmills 1000 of the 1116 employees were left without work, a livelihood and an income.

FROM A SAWMILL VILLAGE TO A PULP COMMUNITY

The Sunila sawmill company got its production running in 1875 with backing from Swedish capital. An industrial community run by the factory owner was created, with its attendant wooden dwellings, primary school and library.

The journey, coloured with several changes in ownership, losses and smaller successes, continued until 1928 when, as a result of a business deal, the sawmill ceased operating and the workforce of almost 300 people was laid off. It was the beginning of a quiet period that lasted for almost a decade and ended only with the economic boom of the 1930s.

The birth of the new Sunila

The Sunila sawmill and its surrounding area came under the ownership of the Kymenlaakso forest industry in 1928. Buyers in the ground-breaking joint venture were the companies Enso-Gutzeit, Halla, Aktiebolag Stockfors, Kymi, Yhtyneet Paperitehtaat, Karhula, and Tampereen Pellava- ja Rautateollisuus. The acquisition of the area seems to have been aimed purely towards future strategic goals.

After the mid-1920s the emphasis of the forest industry began to move from the dominance of sawed timber products towards the production of pulp. The percentage of products derived from the sawmill industry then accounted for 45% of total Finnish exports, whereas the percentage of pulp and paper industry products was under 30%. However, within ten years the figures had changed; sawmill industry products accounted for 25%, and pulp and paper industry products for 40%.

With the beginning of the economic boom in the 1930s Sunila's time had arrived. The joint company owners, A. Ahlström, Enso-Gutzeit, Kymi, Tampella, and Yhtyneet Paperitehtaat decided in 1936 to found the Sunila sulphate cellulose factory, the production capacity of which would be 80,000 tons per year.

The design stages and construction, the quarrying of the rocky building plot on the island of Pyötinen, the completion of road and rail connections, as well as the harbour jetty took only two years.

At its height the workforce rose to 1750, and the completion of the first pulp bail was celebrated on 16th May 1938.

The future, however, is always unpredictable. Economic fluctuations, variations in demand and changes in the global situation with the heavy war years gathered obstacles in the path of bold development. The aimed-for production capacity wasn't achieved until 1951.

Construction of the housing area began at the same time, and proceeded at the same brisk pace, as the factory. Housing for the factory management, office clerks, foremen and part of the workforce was competed in 1937.

FOUR BIG NAMES

The creation of Sunila was crystallised in the actions and personas of four people. It was a team, the members of which were united by an ability to immerse themselves in their specific task in a way that approached near perfection, and to adopt it and to throw themselves into living with it.

Harry Gullichsen, Lauri Kanto, Aulis Kairamo and Alvar Aalto: Cooperation and personal input

Lauri Kanto (1888-1966) - A master on his lands

Lauri Kanto, who qualified as a machine engineer from Helsinki Technical University in 1911 was working as a technical director at Halla sulphate cellulose factory when, in April 1936, he was offered the task of preplanning the Sunila project. Kanto was, in other words, involved in the factory project from the very beginning, came to know it down to its smallest details and grew in time to personify Sunila.

Sunila became a close community which Kanto led with a patriarchal hand. He was the undisputed authority and his word was the law which one didn't question. New workers were made to fit into the spirit and tradition of the old sawmill era under the paternal protection of the managing director. Kanto promoted the leisure-time activities of the factory community; for instance, sports, camping and even photography. In this way social solidarity was formed. But there was also, of course, criticism of this - not everybody was happy about Kanto's way of putting reigns on the community, and controlling its life and everyday practices. The patrons of old sometimes prided themselves on the large number of workers under their employment. This was also the case with Kanto, who strived to make the employees more loyal to the company by giving them slightly higher than average wages.

Kanto and Alvar Aalto worked closely together in the planning of the housing areas. The good working atmosphere was enhanced by a common aim to raise the standard of housing and the social environment linked with it.

The period of Kanto's directorship was long and significant, and only ended in 1961 when he retired at the age of 72.

Harry Gullichsen (1902-1954) - An enlightened protagonist

Economist Harry Gullichsen, the managing director of the huge A. Ahlström company, was a cultivated and socially aware industrialist. He was also chairman of the board of the Sunila company, a position he held for 26 years, until his death. Gullichsen's merits were his leadership and negotiation skills, which were undoubtedly a vital asset in the numerous stages of Sunila.

The choice of Alvar Aalto as architect of Sunila was probably due to the friendship between Aalto and Harry and Maire Gullichsen. For the same reason, Sunila received immediately after its completion excellent international publicity, for instance at the New York World Exposition in 1939. Those favouring the arts were also patrons of architecture.

Maire Gullichsen (1907-1990, born Ahlström), wife of Harry Gullichsen, is regarded as one of the important and influential cultural figures of the 20th century in Finland. She was a cosmopolite who vigorously promoted the transmission of new trends in architecture, the arts and industrial art to Finland. The Gullichsen couple and Aalto were united by an idealised view of society founded on reason, progress and social welfare, which would be achieved by the development of technology and rational planning, and architecture was for them a means to develop society in a better direction. Such progressiveness diverged considerably from the mindset of the leading industrial bourgeoisie of the time. Through the cooperation of the Gullichsens and Aalto, the company aimed for economic and cultural internationalism. The intentions extended all the way to the aesthetical principles of building in the factory society. The cooperation between the architect and industry in solving extensive social problems was ideal from the point of view of the Functionalist programme.

Aulis Kairamo (1905-1991) - A single-minded visionary

Aulis Kairamo knew what he wanted to do already as a student. He realised the sulphate industry was the field of the future, and after qualifying as an engineer he also made himself gain competence in practical work. One gets an idea of how thorough he was by his decision to take on a half-year hired contract at the Halla sulphate factory where he went through all the production sections, as either a foreman or worker.

Kairamo's engagement as the technical director of Sunila began with the actual designing of the factory, after which his task was to organise the actual construction work. Kairamo represented the young engineering generation, as compared to Kanto, which no doubt meant differences in views with regard to the arrangements of the factory and the acquisition of equipment. The work, however, was carried out independently: "Only four times did Kanto interfere with my plans, and each time it led to a mistake being made" recalled Kairamo almost five decades later.

The factory buildings were actually designed in Sunila and the magnificent overall form was due to the specific technical requirements, although the shape of the façade came about from Kairamo and Aalto's joint exploration. The solutions were arrived at by consensus. The magnificent window surfaces were determined by practical requirements, but the designs were by Aalto.

Kairamo later recounted Aalto's flexibility and readiness for honourable compromises: "There was a real architect, who was even able to listen. Alvar was the easiest architect to work together with (in my experience)"

In 1946 Kairamo became the technical director at another large wood refining factory for the Oulu Oy company.

Alvar Aalto (1898-1976) - The architect of time and space

Alvar Aalto's career as an architect began at the beginning of the 1920s, designing in the Nordic classicism style. Among his finest buildings from that period are the Defence Corps building (1924) and the Worker's Club (1924-25), both in Jyväskylä, as well as the Muurame Church (1926-29).

A new trend, Functionalism, came to Finland from Central Europe as a more or less self-evident fact of the times. The main works of Aalto's Functionalist period, Paimio Sanatorium (1929-33) and Viipuri Library (1927-35) brought him to international attention. It was also during the 1930s that his classic furniture designs based on the principle of bent wood construction first came about.

When Aalto came to Sunila in 1936 he was already a well-known architect and cosmopolite, who had already discovered his own design philosophy and way of expression, and had selected what he wanted from the doctrines of Functionalism. One central theme in his thinking was the close connection between dwelling and nature, into which it was natural to link points of emphasis central to Functionalism, such as hygiene, health and light.

Aino and Alvar Aalto had already got to know Maire Gullichsen in connection with the founding of the Artek interior design shop, and through her also become acquainted with her husband Harry. They turned out to be kindred spirits, linked by a love for art, as well as for progressiveness in social matters. On the initiative of Harry Gullichsen, the Sunila board of directors chose his friend Aalto to be the architect of the factory community.

"We'll make this a handsome factory" was Aalto's regular exclamation when visiting Sunila during the initial stages of the planning. His strongest influence, however, was in the creation of the housing area, where he was given basically a free hand to solve the overall functions and appearance, the placement of the buildings and their architecture. The final result can't be called a Functionalist design; it is rather the prototype for a 1940s forest town.

Aalto also made a fine career in the industrial arts, as a furniture designer and glass designer. The Aalto vase, the so-called Savoy Vase, which has become a classic, was born at the Karhula glass works just before he started with the designs for Sunila.

BUILDING

"The actual supervising body for the whole construction work has been the factory management board, the head of which, Harry Gullichsen, has personally followed the details of the work. The actual client representative for the factory has been its executive director Lauri Kanto. The basis for the planning of the building work has been the principled negotiations among the entire board and its executive committee. The person negotiating the details of the fitting in of factory machinery in terms of how it affects the building work has been the factory's technical director, engineer Aulis Kairamo.

The architect has had a very close cooperation with the managing director, Gullichsen, and the head of the factory, engineer Kanto, specifically in regard to the social aspect of building, that is, the residential area and overall planning work."

It was thus that Alvar Aalto outlined a text presenting the plans for Sunila.

The urgency of building and marching orders

The construction of the first stage of the factory and the accompanying residential area occurred at an incredible speed. On the 8th April 1936 the joint owners made the final decision to construct the pulp factory and on 16th May 1938 the first pulp bale was produced.

In April 1936 Kanto, the future director of the factory, took on the task of planning the pulp factory, and already by mid-June he presented a plan for the location of the factory on the island of Pyötinen, as well as a cost estimate for the whole project.

In 1936 the world demand for cellulose was good, and thus the joint owners wanted the factory operations to begin as soon as possible. That, however, required excellent pre-planning and a clear operation strategy for the different planning and construction stages.

As material for Kanto's planning of the Sunila factory, the joint owners bought drawings of Enso-Gutzeit's Kaukopää cellulose pulp mill. In June 1936 the authorization was given to establish as soon as possible an office for the factory. At the same time, the company board decided to discuss matters regarding the architecture of the factory with Aalto and the planning of the building construction with the engineer L. Nyrop.

The site of the proposed factory and residential areas was almost completely in its natural state. Before concentrating on the construction of the factory and the residential buildings, however, it was necessary to build the access connections: roads, bridges, water and sewage pipes, as well as electrical lines. As a local, Kanto was aware of the poor housing situation in the area, and he thus suggested that the construction of housing for both the management and the workers should begin immediately. Already in mid-July Aalto presented to the company board draft designs for the residential area and its first buildings. Construction of the first housing began at the beginning of September 1936.

In regards to the factory buildings, it was decided that the first sections to be built would be the office and factory repair shop. The office was needed as the headquarters for the construction of the factory itself, while the repair shop was needed to assist with the practical building work. The main part of the factory machinery was ordered already in 1936. The actual construction of the factory began the following summer.

At the end of November 1936 the first traditional celebration of the completion of the roof took place. The beginning of the construction work was difficult. Early snow fall came unexpectedly and at times there were problems getting the plans to the building site.

The director's house (known as the 'A' building or 'Kantola') and the row house for engineers ('B' building or 'Rantala') were competed in the winter of 1936-1937, the row house for foremen ('D' building or 'Mäkelä') a little bit later, in the spring of 1937. The heating plant and maintenance building ('C' building) situated between the aforementioned buildings also belonged to this group.

In March 1937 the company board approved the facade drawings of the factory. At the same time it was decided that the house-building programme would continue and workers' housing blocks (the Mäntylä and Honkala blocks) were to be built. The total number of homes was increased to sixty, and it was stipulated that they were to be supplied with hot running water. Mäntylä and Honkala were the last buildings of the first building stage to be completed.

The repair shop was the first of the factory buildings to be completed, in spring 1937. As mentioned above, it was indeed necessary as a work-tool maintenance workshop serving the rest of the building construction. That same year a private railway line was built together with the Karhula OY company from the Kymi railway station via the Karhula factories to Sunila. The completion of the roof was celebrated in August 1937.

On the eve of the completion of the factory, which took place the following spring, Kanto put the case to the board of directors for the continuation of the residential building programme. In May 1938 Sunila Oy decided to participate, together with Karhula Oy and Kymi Oy, in the founding of the Etelä-Kymi housing company (EKA). Five residential buildings for the company staff, together with a maintenance building, were built north of the sports field, the large part during 1939. Kanto was selected chairman of the new housing company. Even though the factory was being completed in a rapidly worsening economic situation and growing political uncertainty, Kanto systematically promoted the improvement of the housing conditions of the workers.

An everyday routine of operations in the new factory and everyday life in the residential area had been established before the start of the Winter War (1939-40). The war, however, brought the routines to a halt. The war and the uncertainty following it disrupted the operations at Sunila for over a decade.

The division of labour and building techniques

Kanto and Aalto agreed already early on that the buildings were to be designed with as little bureaucracy as possible. Therefore, cutting down on costs, the first building had been carried out with as few documents and drawings as possible, and there are not necessarily any complete working drawings for some buildings (e.g. Rantala). On the other hand, the social aims of Kanto and Aalto are evident in how carefully the floor plans of the workers' housing were studied or in how the stairwells of the buildings were designed.

When studying the placement of the factory, Kanto also drew up accurate sketches for a general plan of the residential area. Even though Aalto had a comparatively free hand when it came to designing the residential buildings, Kanto studied, for instance, the placements of the stoves and general spatial organisations in the workers' saunas, as well as the emblem that the company needed. The cooperation was fruitful in many ways; Kanto sketched his ideas on paper and Aalto gave them their final appearance. Aalto was in other ways, too, an expert in applying what he saw and experienced, combining solutions in completely new contexts on the basis of the original idea.

The processes and spatial layout of the factory were to a large degree based on the plans of the Enso-Gutzeit Kaukopää factory (1934-36, architect Väinö Vähäkallio). Thus Aalto's main contribution entailed designing buildings independent of the factory processes, such as the office building, the repair shop building, the Glauber salt storehouse and the pulp warehouse. In the process sections of the factory building Aalto's room for manoeuvre was far smaller because the spatial needs of the functions were already pre-determined. For these buildings Aalto was responsible for the choice of materials, fenestration and the fine-tuning of the overall massing.

The factory's own drawing office was already at an early stage noticeably independent, designing changes and extensions. The more modest designs were often made in the drawing office and Aalto's contribution could consist of general advice on the overall massing, materials and fenestration. Examples of changes carried out by the drawing office were, for instance, the raising of the roof height of the Rantala housing block in the beginning of the 1950s and the extension to the workers' sauna. In the factory, the extension to the office was carried out by the drawing office following the original massing and detailing.

From building on site to prefabricated elements

As well as showing the development of the pulp-boiling process, the Sunila pulp mill gives an excellent cross-section of building from the 1930s to the 21st century.

The factory from the 1930s was built on site with a reinforced concrete and brick construction. The major part of the buildings received red-brick façades. Only the tower-like technical buildings and warehouses were left with concrete facades, which were then whitewashed. The structural solutions were traditional; only the forms became more pared down with time, in the contemporary Functionalist style.

The buildings of the residential area were separated from the factory buildings, and their red-brick or lightweight concrete block surfaces were rendered and whitewashed. The buildings were placed spaciously in the terrain, and the main facades of the buildings were directed towards the southwest or west to maximise daylight. In later projects, too, Aalto continued to demarcate the different functions of a building complex through the use of different materials and colours; e.g. at the Jyväskylä University campus (1951-) almost all buildings related to sports culture have whitewashed facades and all the academic buildings are in red-brick.

The Sunila factory extensions and its new buildings from the 1940s all the way up until the 1960s continued systematically along the same lines. The extensions of the tall pulp boiling building from the beginning and end of the 1950s were made simply by continuing the existing building mass eastwards. In many buildings, however, it is possible to distinguish the old part from its extension only by the slightly differing colour of the facade brick or from minor new details, as the style, massing and fenestration are based on the original concept.

Many changes occurred at the beginning of the 1960s. Kanto, the 'squire' of Sunila, retired in the spring of 1961, after a long and full service with the company. With his retirement, the role of architectural consultant moved from Aalto to architect Bertel Gripenberg. The end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s was a time of development in terms of both pulp production and building. The recovery boiler renewal carried out in 1963-66 fittingly symbolized the changes: the new recovery boiler equipment didn't fit into the old building, and so the height of the roof was raised by some ten metres with the help of prefabricated concrete elements: this extension was the last building in Sunila with which Aalto was involved. Following Aalto's suggestion, Gripenberg rounded off the external corners of the extension.

With the changes in the processes and the increased need for space, the style of the architecture changed. Stage by stage, the factory functions were moved out from the original factory halls, which were then left empty. The new factory buildings from the 1980s and 1990s are of a prefabricated construction, yet have with their red-brick facades been to a large extent adapted to the old factory surroundings.

The old red-brick "ocean liner" is now disappearing between the boiling and bleaching towers and the recovery boiler building.

An intensive and mysterious building stage

The economically stable circumstances and the culturally enthusiastic atmosphere of the time created the basis for the founding of the whole Sunila area. The timetable for the project and the influence of various experts working for a common goal created the world's most famous pulp mill milieu. The war crudely terminated the initial stages of Sunila, but at the same time it increased the mystique of, and interest in, that period.

PRODUCTION

THE SUNILA FACTORY

The Sunila sulphate pulp mill was founded in order to produce unbleached kraft pulp as a raw material for the five companies owning it - A. Ahlström, Enso-Gutzeit, United Paper Mills, Kymi and Tampella - as well as for export. The timber that was to be refined in the mill was transported via waterways and railway, mainly using pine props from the Päijänne water system, and which the partners acquired in connection with other timber acquisitions. 80,000 tons of pulp were produced annually, but the plans for the mill took into account a possible expansion of the annual production to 120,000 tons.

The debarking plant began operating at the beginning of May 1938 and the first batch of pulp came from the drying machine on May 16th. The latter is considered the first day of the mill's operations and the date used to mark the anniversary of the mill.

FROM TIMBER TO PULP

The method in the early days by which the timber was transformed into pulp could be simplified as follows: The timber was floated along the River Kymi in 15-ton bundles and then lifted with a cable crane into the wood yard to be stored, or was transferred with another type of crane directly to the de-barking plant, where the wood was cut and then transferred to debarking drums where it was turned into screened wood chips and then moved via silos into boilers. In the boiling agent the lignin dissolved from the wood leaving the solid matter, the cellulose fibre. The fibre mass was then pushed into washing vats. The washed cellulose fibre went via different sieves to a precipitator and from there to a pan grinder and finally to drying machines. With the first so-called Kamyr continuous digester the cellulose fibre was compressed together when wet, which reduced the water content to 50%, while the ready cellulose fibre coming from the fan drying machine only contained 10% water. The material was then cut into sheets which were pressed into 200 kg bales and taken to the stores and from there onwards to paper mills.

The boiling agent separated from the cellulose was recycled through an evaporation plant and the remaining lye was dried. The dried lye and the condensed lignin were burned in a furnace and the heat energy produced from it was recovered. When the separated chemicals were mixed in water it produced a sodium hydroxide solution. This was caustisized with lime, clarified and thus attaining a usable boiling agent. The boiling agent continued its unending cycle within the factory and losses were replaced with Glauber's salt, but the timber was taken as pulp bales out into the world via railway or onto ships in the factory's own harbour.

The production of chemical pulp follows similar principles today. Today, however, the factory is automated, all parts of the process have been completely renewed, the pulp is bleached and the waste water is biologically purified. There have also been air pollution protection stipulations to take into account.

The factory is energy self-sufficient. The black liquor retained from the boiling agent is treated in the evaporation plant to a suitable level of dry content and it is then burnt, thus producing steam for the factory turbines and the production of electricity.

THE STORY OF THE FACTORY

The difficulties of the early days - recovery and expansion - and the present

The beginning of factory operations was difficult: the demand for pulp was small and production had to be limited. During the Winter War the factory operations were mostly suspended and a large part of the workforce was in the front-line troops or otherwise engaged in the service of the Finnish defence forces. Even though Kotka was perhaps the most diligently bombed civilian target in the war, Sunila escaped notable destruction. Apart from a stoppage in production in the winter of 1942, the factory continued to operate during the Continuation War, not only for economic reasons but perhaps also as a symbol for the continuation of life in peace-time. During the war years Sunila was run to a significant extent by women. As much as 65% of the staff operating the machines were women - under normal circumstances they made up 10% of the total workforce.

When the war ended the pulp market picked up. High inflation as well as difficulties in acquiring timber, coal and lime, however, slowed down the development of operations. In 1951 the factory reached its original annual production target of 80,000 tons and that same year the first extension project was initiated, after the completion of which, three years later, annual production increased to 120,000 tons. State-of-the-art laboratory facilities were set up on two floors of the new office wing.

Sunila was the first sulphate pulp mill in Finland after the war to start bleaching the pulp. With a method developed in the factory laboratory, a semi-bleached pulp with the brand name Semi-T was produced; in 1950 this accounted for 10% of the total production.

The next stage of expansion in 1958-1960 raised the annual production to over 200,000 tons. At the turn of the decade the large-scale projects included the renewal and extension of the power plant and the construction of a new turbine and water purification plant. Production records again rose with the extension of the semi-bleaching plant. The new state-of-the-art full-bleaching plant started operating in 1970, and this large investment was followed by the construction of a large wood-handling plant. Like in many other fields, automation and information technology took over also in the pulp processing industry, and environmental issues began to become more pronounced also in investments. From 1978 onwards the effluent from the process was led to a new mechanical purification plant, and the biological activated sludge plant began operating in 1995. Today the emissions from Sunila are at the same levels as in other modern factories.

The renewal of the subsections of the production was begun in the 1970s. The extensive investments, the modernisation of technology and the reduction in the number of staff was undertaken in order to increase production and quality. A new recovery boiler was built in 1988, and the fibre production line was completely renewed the following decade. A continuous action boiler replaced 13 old single-batch boilers.

THE FUTURE OF THE PRODUCTION

The annual production capacity of the Sunila company in 2003 is 350,000 tons, for which 2 million cubic metres of spruce and pine is needed. Over 50% of the wood and chips arrives to the factory by road, 15% by rail and 30% by sea (mainly from the Baltic States) via the factory's own harbour. The ready pulp is delivered mainly by road to clients in Finland and a part is shipped abroad.

In 2002 the factory, owned by the Myllykoski Paper company and the Stora Enso company, had a permanent workforce of 300.

The factory lives in its own time, and time leaves its mark on the appearance of the factory. Original working methods required facilities of a specific size, into which, however, it is not possible to place new equipment. Large factory halls have been abandoned and the newest extensions have been built outside the red brick envelope of the original factory building, and new massive 35-metre-tall silos, built for storing wood chips, have been located even further away.

WORK

"They have control rooms where they follow the process on monitoring gauges so one doesn't have to go and look every now and then to see how the pumps work: but before it was done by rule of thumb, so that when they did the boiling they could put the valve like that, and when the next boiler came then they turned it in a different position, because each shift had their own style… and when the pulp was washed in such a washing vat they looked into it and hosed it and let water in in different ways, whereas nowadays everything goes through a filter of course, they're not touched for weeks, they progress…"

This was how a retired Sunila employee, recalled, in 2003, the changes which happened in the factory during his working life from 1956 to 1983.

In the early years and particularly when the factory was starting, the workers often learnt their skills by practice and work experience. The staff coming to work in specific tasks consisted at least partly of skilled workers who had been trained for several months in the other sulphate factories belonging to the joint company owners. The major part, however, would have had no previous experience. These would have been mostly locals who got their first hands-on experience as unskilled labour in the installing stage and received the final experience working with the machines, and were thus trained through practical work.

Usko Haapanen recounts: "In February-March there were 14 of us in Kaukopää, each studying a particular task. I studied the management of evaporation… for five weeks. We were very keen. By studying and trying ourselves we learned what the task demanded in practice. Typically you usually did not tell the next bloke of the nifty tricks we had discovered ourselves. We learned the basics in Kaukopää and the rest at home in Sunila."

Workers were also transferred from the old Halla sulphate factory, which was being run down in pace with the starting up of Sunila.

The on-the-job experience and rule of thumb approach of the workers were valued and the smooth running of things in fact depended upon them. Man was present in all the stages of the pulp-making process. In the beginning the factory had a workforce of 450, after the first expansion after 1954 it rose to 760, and at its height, in the beginning of the 1960s, it was 1240.

"WE DID OURSELVES WHAT WE COULD"

Pulp making continued as an essentially hand-made process until the 1960s. Once the renewal of the working methods began it then reached to every aspect of the production, but could most clearly be seen in the beginning and end stages of the process. In unloading the timber different machinery replaced people and pulp hooks, and the moving of the pulp bales was carried out entirely with fork-lift trucks.

Since the 1970s automatization and computerization have entailed the replacement of hundreds of workers. In the present pulp-making process, the workforce is mainly needed to observe and follow the process with monitoring devices, inspecting the quality of the product and doing any necessary maintenance work of the processing machinery.

Even though there has been a manifold increase in production, there is nowadays a workforce of about 300, considerably less than when the factory began its operations.

Many of the stages of the work process that no longer exist were difficult and heavy. Inspecting the ready 200-kg pulp bales, weighing and pushing the material onto the press was considered "delicate work and often even women's work". In the same way, transporting the bales from the harbour warehouses to the ships required both skill and perseverance, on top of being heavy work.

There was a foundry in the machine repair shop, but this was closed down in the 1960s. Even some pump models were made in the foundry, in moulds made by the factory's own joiner. All in all, self-reliance and self-initiative was seen as part of the job during the era of the patriarch Kanto; his principle was that they themselves should try and make everything that it was possible to make.

The few hundred men in the repair workshop - lathe workers, milling operators, filers, planing-machine operators, fitters, plumbers and sheet metal workers - repaired and made new parts when needed, even improvising as necessary. As the technology used in the factory at the time was simpler and more straightforward than it was later to become, the electricians developed their own gadgets and equipment, apparatuses for the machines that transported pulp bales and other things.

THE COMMUNITY

THE GOLDEN ERA OF THE COMMUNITY

When the planning and building of the Sunila factory and the housing area linked with it began in 1936 it meant the birth of a whole community and a renewal of life in the area. Situated on an islet, Sunila was a separate area in itself and there was no attempt to link it to the rest of the municipality. This physical separation strengthened the patriarchal spirit endemic to the saw mill trade, which was reinforced in turn by the character of the managing director of the new factory, Lauri Kanto.

SERVICES, EDUCATION, LEISURE-TIME ACTIVITIES

The company offered its workforce basic services, health care, a children's day-care service, a centralised laundry and sauna facilities and a variety of organised leisure-time activities. The company newsletter, Sunilan Viesti, was published for the first time in spring 1945, and covered both work and leisure-time subjects. The articles emphasised cooperation, responsibility and togetherness. Trade union activity was lively and the Sunila chapter of the Finnish paper industry workers' union was founded in 1941.

The Sunila spirit was built systematically. It was personified in Kanto, whose paternal touch and presence was felt everywhere, both in larger and altogether minor matters. Kanto is remembered as a patriarch who looked after the well-being of his workers, and who was prepared to take small risks when necessary.

Aulis Kairamo, the technical director in Sunila, recounted the story of how Kanto acquired a bus, used for instance for the workforce to go on mushroom- and berry-picking trips as well as a school bus. When the company board of directors visited Sunila the bus was hidden in the forest on Kanto's orders. When Kairamo raised the issue with Kanto he answered: "You are not a tailor's son like me. I've seen poverty and I'm on their side. You are the son of a senator."

Sunila was an active and self-reliant but closed and cliquish community, which offered work, services and leisure-time activities. Outside transport connections were taken care of by a year-round bus service and in summer also with scheduled boat traffic - and some of course had their own form of transport, a bicycle and kick sledge. Motor traffic took over gradually from around the mid-1950s.

The company was responsible for several social and leisure-time services which nowadays would be perceived as being the responsibility of the state. For ten or so years after the war Sunila was a self-reliant community, almost completely under the guardianship of the company. This was to bind the staff together and build a beneficial 'we'-spirit. Many former employees remember this period as the happiest at Sunila.

A SELF-RELIANT COMMUNITY

The war taught self-reliance

Self-reliance was a natural aspect of life in Finland up until the beginning of the process of urbanisation, that is, the 1950-60s. Especially the shortages following the 1939-45 wars forced people to be active and inventive. People gathered from nature what they could, and made garden allotments wherever they could. Matti Kanto, Lauri Kanto's son, described the situation in his memoirs as follows:

"We were in the middle of war time and bad shortages. The worst winter for food was the winter of 1942. Hoarding trips were made in the vicinity and further away by bicycle. Allotment gardening was also begun, and there were allotments for instance along Sunilantie road, in the yards of the houses and elsewhere. Domestic animals were kept where possible. Pigs were everywhere, for instance on the EKA hill. We had a goat, which ate all the food scraps and whatever we could get hold of…"

Keeping pigs was popular, but placing pig sties amidst the dwellings was a problem. The paper-workers' union presented a letter to Kanto in 1946 with 144 signatures asking for permission to keep pigs. The communal pigsty recommended by the Kymi health board was, however, never built.

The residents of Sunila had over 400 potato and root-vegetable plots immediately after the war in the Sunila area. The home-economics expert hired by the company helped and held courses in matters related to cultivation and clothes maintenance. When there was a shortage of everything, recycling came about naturally; for instance, the old felt from the drying machine was found to be a good and durable material for clothes and carpets. When the Martta organisation (a nationwide organisation founded in order to promote good housekeeping) began in 1942 home economics information was efficiently spread throughout the country.

The Sunila company transported the workforce and their families with its bus to gather forest berries and mushrooms, and the Sunilan Viesti kindled its competitive spirit. In the summer of 1943 there were 35 berry-picking trips and about 1700 people participated, picking about 23,000 litres of berries.

The inhabitants of Sunila also distinguished themselves in the national firewood campaign, which aimed at preventing a fuel shortage. By the spring of 1944 the target of 6000m3 had been passed and several people received awards: two of the inhabitants of Sunila received the so-called 'grand axe' badge and ten received the 'gold axe' badge. To receive the top award one had to chop 48m3 of firewood and for the second award 16m3.

CHANGE, VARIETY AND RECREATION

A change of scenery and recreation - Kesäniemi

To get out into freedom, to the sea, to the fresh air, were surely thoughts in the minds of many inhabitants in Sunila as spring came. The dwellings were after all constricted in relation to family size and the smoke coming from the factory flues was not as clean as it is today.

The company acquired in 1946, and later bought, a shoreline plot where it founded a summer holiday resort for its employees. The place was named Kesäniemi and was located at a suitable distance from Sunila, 10 km by boat, and therefore clearly separate from the factory.

Kesäniemi grew within a couple of years into a 16-hectare recreation area, and in addition to the sauna modest over-night cabins were built. Nature, however, was the most important aspect. People spent the night in tents. Cabins were rented for a week at a time, in which case families with children were given priority. Children's summer camps were arranged from the very beginning. The journey was made with the factory's regular service boat (though some had their own boat) with picnic lunches, cooking utensils and other camping gear along.

People swam, used the saunas, fished, played games and sports, danced on the open-air dance floors, and generally enjoyed summer. Sailing courses were arranged with two sailing boats called Sipi and Sotka, made available to all staff, and mid-summer feasts with bonfires and other traditions were arranged.

Kesäniemi was developed in the 1960s by building guest cabin facilities and, in connection with these, a janitor's flat. The large new camping ground shelter could be used for many purposes. In many ways an important change took place with the completion of the access road, because people no longer arrived only by sea or along a forest path.

SPORT

Sport took place in Sunila both in the competitive sense as well as for recreation. The most popular sports were (in winter) skiing, and amongst young people also skating, ice-bandy and even ice-hockey. Skiing competitions with their many different classes, were the highlight of the winter and people actively took part in them; the usual number of participants for the Sunila winter sports event rose to over 300. The most daring youths were drawn to the ski jump, with a 5-metre high take-off tower, built by the company, from which jumps of over 10 metres were made.

In summer athletics, football and baseball were the most popular sports, played in the meadow sports field of Koivuniemi. Each summer in the "Sunila Olympics" initially held there, but later held on a gravel field built next to Sunilantie Road, there were some events, such as triathlon and middle-distance running, that attracted a couple of hundred participants. People competed individually in classes determined by age, while the team sports were carried out between the different factory departments. Orienteering became extremely popular and there was success in this sport even outside the Sunila area.

At its peak, the Pirtti community hall was in almost continuous use for different sports. There were practice times for women's, men's, girls' and boys' gymnastics groups, wrestling, weightlifting and boxing every week-day night.

The Sunila Sisu sports club was founded in 1937. Already the following year it was chosen to arrange the Finnish championships in apparatus gymnastics, and these were held in the Sampo community hall in Karhula and in Sunila. After successfully hosting the event, the Sunila company hired the gymnastics instructor Esa Seeste, who had been successful in the championships, as a full-time sports instructor in Sunila.

The arrangement produced results; well-known sportsmen were brought to the Sisu sports club and for a few years Sunila became the centre of apparatus gymnastics in Finland. Sunila Sisu won the Finnish team championship in the discipline three times, in 1939, 1941 and 1945. The top level gymnastics continued in Sunila until the 1960s. The workforce, coming from different parts of Finland, consisted of an unusually large number of good sportsmen. The factory also supported sports activities, and with much competition success.

ROWING

Rowing became an even more prestigious sport than gymnastics in Sunila. What could have been more natural for coastal inhabitants than rowing? On the other hand, the stylish sport also fulfilled the expectations of the company as the builder of morale and as an image builder, and so the sport was worth investing in.

In Kotka the sport had first begun with the whale-boat rowing competitions of the coastal civil guard. In 1939 the Kotka team won its competition series with its inrigged fours. The Sunila rowing team got off to a good start already before the war, but participated in competitions in the civil guard squad.

After the war the rowing activity restarted, but now as an independent team. Sunilan Soutajat [Sunila Rowers] was founded in 1945 and it had already from the very beginning a special position under the patronage of the company director. Kanto created the preconditions thanks to which the rowing team in Sunila rose to achieve great success unbelievably quickly. The company financed the competition trips and other expenses of the rowing club and made available boats and rowing equipment it owned for the use of the club, as well as supervised the continuous maintenance of the equipment.

Top placements in competitions became common. The cox-less four won the Finnish championships eight years in a row. In an international rowing competition held in 1947 the club represented the Lommi squad in both the out-rigger and in-rigger events. Victory came in both events, even though the main opponent was the steel hard rowing crew from Aarhus rowing club in Denmark.

Success did not come without hard work. The head of the rowing club Arvo Mussalo participated in the four-day basin rowing courses held in Finland by the top Danish coach Viggo Petersen, and during the competitions Petersen visited the Sunila rowing basin in use at that time, which had been built in connection with the water purification plant.

The Sunila rowing team participated in the Nordic Rowing Championships in Copenhagen in 1946 and then spent several days as the guests of the Køge rowing club. It was now possible to practice with the hosts' equipment on the coast of the Baltic Sea and to perfect their own rowing techniques by observing their competitors.

The boat equipment increased when the Sunila company joiner Niilo Paljakka completed his own in-rigger for the 1948 season. Unlike other boats, the hull bottom was V-shaped, and judging by the successful results they achieved, it evidently had some effect. The following year Niilo and Anton Paljakka built the first competitive out-rigger four in Finland, called Alli, the design of which was based on models of the well-known German Pirsch boat builders.

The Sunila team represented Finland in the Olympic Games in London in 1948 and came sixth. In 1951 the German coach Kurt Hoffman was hired by the Finnish Rowing Association and visited Sunila, and soon a real test lay ahead, the Olympic Games held in Helsinki the following year. In the finals, Finland and Sunila took the bronze medal. The medal-winning team consisted of Veikko Lommi, Kauko Wahlsten, Oiva Lommi and Lauri Nevalainen.

The success of the Sunila rowing team continued for some years, for instance in Nordic competitions, but they were never chosen to represent Finland in any further Olympic Games. Rowing continues today as a sport in Sunila, but as a leisure sport and with competitions between different companies.

The Sunila company joiner was regarded as an exceptionally skilled boat builder, but canoes were built by hobby enthusiasts. Canoeing began in Sunila in 1948 under the direction of factory economist Georg Gyllström: excursions were made into the archipelago as well as to sites at the mouth of the River Kymi. Eight canoes were built in the canoe workshops using tools acquired by the factory, and with materials for which the factory paid half the costs.

The Sunila Community Today

Sunila, like many other industrial communities of its time, has not come through the great upheavals in modern society unscathed. The efforts to adapt the city district of Sunila to present-day conditions have only just begun. So-called neighbourhood home activities started in 1996 and have been one of the most successful ventures. The "korttelikoti" or neighbourhood home, housed in the EKA heat plant building, offers the Sunila inhabitants opportunities for many kinds of leisure activity, but above all it is a place to meet other inhabitants.

There is also a city district organisation called Pro Sunila, which, in cooperation with the City of Kotka and several other actors, strives to find new directions for development, one result being that Sunila is participating in the national Suburb Renewal 2000 programme, which has enabled also the present cooperation project.

There is an increasing interest in the building heritage and other cultural aspects of old industrial communities, and their building stock has been the subject of several studies and student theses. Work is also being carried out in Sunila to chart the history of the area by, for instance, interviewing people, as well as investigating new uses for different maintenance-, service-, and public buildings. The fact that the Sunilan Sisu sports club has begun to repair the Pirtti community hall gives hope for the future.

HOUSING

FROM SAWMILL LODGINGS TO THE COMPANY TWO-ROOM FLAT

"Well, some people say that even a large family can live in a one room flat, as long as they all get on"

Habitation in the Sunila area goes back, at least during the time of sawmill operations, to the latter part of the 19th century. The workers lived on the Koivuniemi cape, in large two-storey houses that the sawmill had built, with the inhabitants divided according to their occupation. Pikku-Pyötinen was a small, densely inhabited village south of the island of Pyötinen where the Sunila factory was situated, and which was demolished when the factory was extended.

When construction of the factory began the empty houses offered a temporary solution to the immediate accommodation needs. At most 1800 people were involved in constructing both the factory and residential area, and already at that time there was a great need for housing. The managing director of Sunila, Lauri Kanto, was appalled that as many as six men had to share the same small room. There were reasons to be concerned about the well-being of people, but also for the acquisition of a high-quality and permanent workforce.

The Sunila area was originally designed as an independent community with its own housing. The company built housing for its workers in stages, the first at the very beginning of the operations.

Alvar Aalto was commissioned to make the general plan for the area as well as design individual buildings. The residential blocks of flats were freely placed following the sloping terrain, and the lower buildings were placed near the shoreline. The solution is spacious with a feeling of being close to nature, but the hierarchical model of the traditional industrial community is also evident, with housing for the management and the workers separated and the floor area of the flats correlated with the social status of the inhabitant in the community.

HOUSING STYLES

Aalto had studied housing issues already in the 1920s. He knew of the Weissenhofsiedlung housing presented in connection with the "Die Wohnung" exhibition in Stuttgart in 1927, and in 1929 he participated in the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) congress in Frankfurt, which had the theme "Die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum". CIAM promoted the new, rational architecture that strived for social justice.

Aalto actively participated in housing reform. He brought the Central European model, the minimum housing ideology, to Finland via the 'Minimum Apartment' exhibition held in Helsinki in 1930. Also on his initiative, an extensive housing exhibition was held in Helsinki in 1939, which presented social housing based on type house solutions. The exhibition, aimed at the general public, brought attention to the problems in housing conditions together with solutions based on rationalisation and design.

At the Nordic Building Days exhibition held in Helsinki in 1932, the design principles of small rationalised dwellings were presented, as was the concept of Existenzminimum. The intention was to make reasonable housing conditions available to an increasing number of people. It was seen that the means towards achieving this goal entailed an appropriate building technology, a reduction in the floor-area of flats and furnishing them with rationally designed furniture.

Functionalism aimed to extend high-quality planning to everything, including housing for those of lesser means. Both Functionalism and the Garden City ideology emphasised health and the advantages of living close to nature, as well as the connection of people's homes to nature.

Humane ideologies were important to Aalto. An additional impetus to these ideas came when he and Aino Aalto made a study trip to Central Europe in 1935, where in particular they noticed that Swiss architects were moving from a strict rationalism towards a more human-centred direction.

18-450M2

The official residence of the managing director of Sunila, Kantola (450m2), and the five apartments making up the two-storey five-roomed engineers' row house, Rantala (185m2, 200m2, 200m2, 220m2, 280m2), both built in the first building stage (1936-37), still today represent a spacious, even luxurious, housing design. The dimensioning of the 14 two-storey terraced houses for foremen, Mäkelä (85m2) (1937), is already a lot more economical.

Aalto got to test the actual combination of strict dimensioning and careful planning in connection with the small Honkala and Mäntylä apartment blocks, which were also completed in the first building stage. 42 of the flats consist of two rooms plus a kitchen (45m2) and 20 are one-room flats (30m2) with small kitchen 'alcoves'.

The same compact line continued in the second building stage (1937-38). Three blocks of flats, Kontio, Kivelä and Harjula, were built around their own boiler plant, as were two three-storey row houses built on a slope, Karhu and Päivölä, with a total of 160 homes ranging in size from 30m2 to 45m2.

The level of facilities in the dwellings was for its time progressive. All buildings had central heating, electric cookers, running hot and cold water as well as a toilet. The small size of the sanitary facilities is probably explained by the fact that there were two laundries and a large sauna with washing facilities for general use in the area. There were even American refrigerators in the homes of the foremen and the highest ranking employees: at the time these were available to only a few in Finland.

"It was of course fine that the toilets were indoors. But it was odd at first to live in a block of flats when neither had lived in one before. Water came in, there was warm water, the sauna was just next-door, the laundry was next-door."

Today one couldn't imagine a one-room flat as a family dwelling, and a two-room flat just barely. In the 1930s, however, they were a considerable improvement in the worker's average standard of living, and the rooms were felt to be spacious, airy and light. Nowadays Sunila comprises typically of 1-2-person households.

It was not exceptional for a 6-person family to live in a 45m2 two-room flat. One of the rooms was kept as the 'better side', with perhaps a couple of armchairs, a book-case and a pull-out chaise longue, which in the evening was pulled out as a sleeping place for the children. The other room contained the dining table and the parents' sleeping place.

"One felt there was quite enough space, because there were all the comforts that very few people had in those days. There was an indoor toilet, and water came and went. Usually people who lived outside Sunila had to carry the water in and had an outdoor toilet. Well, some people say that even a large family can live in a one-room flat, as long as they all get on."

The Kuusela apartment building, completed in 1947, was built to remedy the post-war housing shortage. The Juurela and Runkola apartment buildings, completed in 1953, were the last to be built and came under the (Arava) state-subsidy programme. The floor plan layout varied, as did the size of the flats (18-105m2), but with regards to the fittings they didn't much differ from the general level at that time. What was new, however, was that in these houses lived both working class as well as white-collar worker families. The barriers in the industrial community of 1700 inhabitants had been lowered.

EXPECTATIONS

One of the large changes in Sunila in the 1960s was the company's decision to give up ownership of the housing stock. In the winter of 1970 the houses and flats were gradually put up for sale, first to company employees and then also to outsiders.

The company's new housing policy was centred on supporting workers to acquire their own homes. Also in the plans were proposals for combining the one- and two-room flats owned by the company.

The decrease in the number of factory employees, as well as the general population number in Sunila, and the simultaneous accelerated change in society into a motorised one offering centralised services, led to a situation where the area began to wither. The shops closed down. Public transport decreased, and likewise other public services. The social value of the area collapsed.

The suburb renewal, begun in 2002, aims to return the value of the area. The planning of the repair of the flats offers solutions for the modernisation of the kitchen and bathroom facilities, as well as for even combining flats. Large alterations, however, are not favoured because the permanent value of the flats lies in their beautiful proportions and in how finely the view opens up into the spacious surroundings from the windows which are well proportioned in relation to the room space. This preserves the connection to nature cherished by Functionalism.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Published and unpublished sources:

Aalto Alvar, Sunilan sulfaattiselluloosatehdas [Sunila sulphate pulp mill]. Finnish Architectural Review, 10/1938.

Alava Paavo, Sunila metsäjättien yhtiö [Sunila: The company of forest giants]. Gummerus 1988.

Hipeli Mia, Sellua saarelta [Pulp from the island]. Alvar Aalto Kotkassa. Exhibition catalogue, Sirkka Soukka (ed.). City of Kotka, 1997.

Kanto Lauri, Kirje Kymin kunnan terveydenhoitolautakunnalle 23.4.1946 [A letter to the Kymi Municipality Public Health Board], The Provincial Museum of Kymenlaakso, 1946.

Kanto Lauri, Promemoria Sunila Osakeyhtiön asuntotilanteesta 15.4.1938 [Memo on the Sunila Oy housing situation]. Sunila factory archive, 1938.

Kanto Matti, Silppua sahalta, tikkuja tehtaalta. [Chips from the sawmill, sticks from the factory], Unpublished copy. No date.

Kaukiainen Asa, Sunilan Soutajat [Sunila Rowers]. Manuscript. No date.

Korhonen Martti & Saarinen Juhani, Kymistä Kotkaan, osa 1 [From Kymi to Kotka. Part 1]. Porvoo 1999.

Kymen Sanomat 24.10.2002.

Mikkola Kirmo, Funktionalismi [Functionalism]. In, Suomen taide. Otava 1990.

Mikonranta Kaarina, Sunila Oy:n sisäkuvat [Sunila Oy Interior views]. In Alvar Aalto Kotkassa [Alvar Aalto in Kotka]. Exhibition catalogue, Sirkka Soukka (ed.). City of Kotka 1997.

Saarenmaa Antti Sakari, Sunilan tehdasyhdyskunnan alueellinen kehitys [The regional development of the Sunila factory comumunity], Department of Social Policy, advanced studies, Helsinki University, Faculty of Social Sciences, 1969.

Savolainen Mervi, Tehtaan huoneista omaan kotiin [From factory rooms to a home of one's own]. Diploma thesis, TKK 1993.

Schildt Göran, The Mature Years. Otava 1985.

Sunila Osakeyhtiön esittelyteksti [Sunila Oy presentation text]. Unpublished copy. Sunila factory archive. No date.

Sunila Oy, Lyhyt historiikki [A short history]. Unpublished copy. Sunila Oy 2003.

Sunila Oy, Toimintakertomus 2002 [Sunila Oy, Annual Report 2002] . Sunila Oy 2003.

Sunila Oy, Ympäristöselonteko 2001 [Sunila Oy. Environmental performance statement 2001]. Sunila Oy 2002

Sunilan Viesti 1/1945, 3/1947, 1/1948, 2/1951, 2/1953, 3-4/1953, 1-2/1954, 2/1957,

3/1957, 3/1976, 1/1978, 1/1979.

Woirhaye Helena, Maire Gullichsen. Taiteen juoksutyttö [Maire Gullichsen. An errand girl of art]. Museum of Industrial Arts, 2002.

Yli-Lassila Jukka, Asuntoprobleemi, standardisointi ja Alvar Aalto [The housing problem, standardisation and Alvar Aalto]. Masters' thesis. Jyväskylä University, Art History Department, 1995.

INTERVIEWS

Alava Paavo 12.5.2003

Kirjavainen Pentti 4.6.2002

Mäkelä Esko 1.4.2003

Väätäinen Esko 27.3.2003

Göran Schildt interviews Aulis Kairamo in regard to Alvar Aalto at the Savoy restaurant, Helsinki, 26th August, 1983.

TRANSLATION FROM FINNISH: Gekko Design / Kristina Kölhi, Gareth Griffiths

» PDF (3,7Mb)

|

|

|