MART KALM

Architecture historian

Professor

Estonian Academy of Arts

PÄRNU RESORT FUNCTIONALISM

In the 1930s two things happily coincided in Pärnu: the city developed as an international holiday resort and Olev Siinmaa, one of the great Estonian Functionalists, became the Pärnu town architect.

Although beach resort architecture in Pärnu had historical roots, Functionalist aesthetics did not meet any opposition here. Beach resort culture was novel for Estonians: it had always been a pastime for well-to-do Germans. Once the urban population had grown and become more affluent, more and more people had the opportunity to holiday instead of working on their relatives' farms in the country.

Olev Siinmaa (1881-1948), who was of the same age and had a career similar to the generation of architects trained in Riga, came from a joinery shop owner's family in Pärnu, and studied in Wismar and Konstanz technical schools in Germany. In 1925 he was appointed the Pärnu town architect. As Siinmaa had no architect's qualifications, he was not perhaps entirely trusted by the government. His educational background was in interior and furniture design and he was outstanding in both. To a certain extent, Siinmaa's work bears the mark of a dilettante, but he was undoubtedly one of the best architects in Estonia at the time.

Siinmaa's first Functionalist villa, designed in 1930 for the industrialist van Jung, is not located in Pärnu, but in Tallinn, at 4b Roosikrantsi Street. The most attractive feature is the entrance which is a projecting curved bay with a strip window above the front door. This bears witness to the architect's wish to juxtapose the rationality of the building with a playful modern element. Even more decorative are pastel-coloured Art Deco window grates in the lounge and the porch, contrasting with the dark-coloured frames. They were not designed to protect against burglars, but rather to smuggle fashionable ornament, which was thought to be beautiful, into a style that denied all facade decoration. This gave an opportunity for an affluent industrialist to flaunt his wealth in a language that everyone would understand.

The next building erected according to a 1931 design, for Siinmaa himself at 1a Rüütli Street in Pärnu had quite different concerns. The problem to be solved had much more to do with Functionalism: how to design a rational dwelling for a family on a small triangular corner site. The inconvenient acute-angled site had long been empty and surely the town architect was the right man to demonstrate his capability. He placed the house against the sidewall of the neighbouring building and, as a bonus, got an additional front garden on the corner.

The reform-minded Siinmaa found fresh solutions for all functions. Thus he designed the drying room for the washing on the roof terrace, the middle room in the basement was considered to be a "courtyard" and a number of rooms opened into it: a room for firewood, a laundry, a cellar, a tank for rainwater and a workshop with a lathe. On the ground floor the study and the dining-room are recesses off the lounge so that the flow principle is used effectively. As the dining-room recess was at the rear, an inner window opening to the hall gave additional light. Siinmaa made frequent use of the inner window motif, which rendered the house transparent and semantically multilayered. Food was served through a special revolving hatch of rounded glass in the sideboard. Siinmaa's kitchen, although small, was rationally constructed and was the first modern kitchen in Estonia. Several of the elements such as seats and the ironing board were collapsible as in the so-called "Frankfurt kitchen".

While the angularity of the facades in Siinmaa's house, which was partly due to the irregularity of the site, carries the dramatic restlessness typical of Expressionism of the previous decade, the villa at 2a Lõuna Street (1933-36) is definitely one of the smartest Functionalist villas in Estonia. Similarly to his own residence, the villa in Lõuna Street is placed in such a way that it is lighted through windows only on three sides. Thus the dining room is in the gloomy middle part of the house and is lighted through a round glass window in the hall. This not only serves as a window but also as a glass-shelved showcase for the crystal glass ware; as it was lighted inside it was practicable and permitted the owners to display their wealth. The inner window motif is repeated with an opening leading from the study to the conservatory. Although the floor plan follows the conventions (utility rooms and formal rooms are strictly separated, the servants have their own entrance, etc.), the rooms are placed in free clusters.

The facade of the villa is an outstanding example of modern geometric compositional design. The only traditional feature is the dark-painted socle of varying height, whose purpose is to avoid the soiling of the walls by mud.

There are more, fairly good Functionalist villas in Pärnu, mostly designed by Siinmaa's followers (M. Merivälja, I. Laasi, J. Kinnunen, et al.), who took up their careers after graduating from the Tallinn Technical School.

Pärnu became a fashionable resort town after the completion of the grandiose Beach Hotel in 1937. By drawing upon the ideas of the 1934 competition, Siinmaa and Soans drew the final project. All the rooms open to the sun and the sea: the balconied seaside facade is open and the inland facade is enclosed, with its narrow strip windows in the passageways. As the building, which was located in a seaside park, was to be presentable from all sides, the courtyards and garages are concealed behind the walls, which, in their turn, enhance the sense of enclosure in the inland direction, reminiscent of southern architecture. An appropriate allusion to ship building is the rounded finish given to the projecting central part.

One of the peculiarities of Estonian Functionalism is the lingering existence of Traditionalist interior design elements. Although the furniture used in public buildings was an attempt at gracefulness in harmony with architecture - wickerwork seats or the spoke-like armchair backs -, the lower lounge used traditional lighting and the stairwell was ornamented by an Art Deco seascape by Peet Aren in a Neo-Baroque frame.

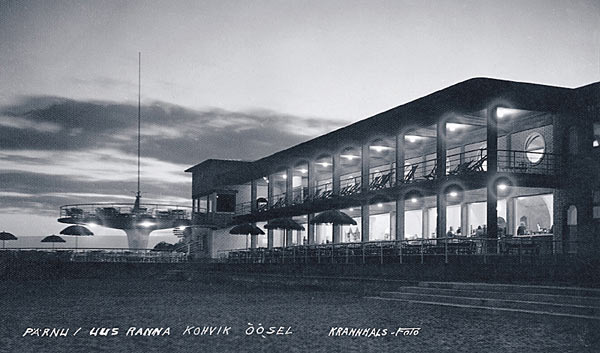

While the Beach Hotel was Modernist in its social and aesthetic aspects, Siinmaa's Beach Pavilion completed in summer 1939 adds the flavour of Modernist technology. This construction is entirely of ferro-concrete. The cafe section is covered by a sloping ceiling-roof, which shows the building as one-storeyed from the inland side, rising to two-storeys on the seaside. The cafe interior has an inner balcony on the seaside, and this continues on the outer side as a broader terraced balcony boasting wide porthole-type windows. On the corner this is adjoined by an intriguing concrete construction, a mushroom-like balcony which provides shade underneath and a sun deck above. As an essential Modernist device the whole building features stark concrete surfaces.

Under the pressure of the nationalist ideology of the age Siinmaa designed a reading room for the library in "purely Estonian" spirit, and here, too, he was able to avoid sentimentality, by covering the ceiling with bare pinewood boards.

In his Functionalist holiday resort architecture of Pärnu, Siinmaa gave a new life to wood, along with concrete. Although wood as a natural material seemed too traditional in an age carried away by enthusiasm for technological progress, it was a convenient material to imitate the machine aesthetics of concrete, and for this reason it was widely used in the Nordic countries. Rounded surfaces and strip windows provided liveliness to the wooden stand of the Pärnu stadium, which rejected the traditions of wood architecture.

|